After Machu Picchu, we returned to Cusco, to collect our luggage, and move on to our next leg: Bolivia. We planned to travel to Bolivia see the Salar de Uyuni, the worlds largest salt flat. Lana had read about it and put it on the list, and we had heard glowing reviews of it from all of the travelers we’ve met who have been through Bolivia. We really wanted to see it, but we’d also heard amazing things about Colca Canyon and Arequipa in Peru, and we knew we had to be in Buenos Aires by the 29th of November to make our flight to Patagonia. Our time was limited, and we debated chucking our plans that we made before we left, and heading off to places we’d heard about from other travelers. After much hemming and hawing, we decided to go with what we knew we wanted to see. If we bailed on Bolivia now, we would probably always wonder if we should have done it. Plus, we planned to see Lake Titicaca along the way. So we bought bus tickets to Puno, on the shores of lake Titicaca for the next morning, and enjoyed the remainder of our day in Cusco.

Our bus ride was 6 hours, and was reasonably pleasant. The semi-cama (half bed) seats were similar to coach class on an airplane, and the scenery was pretty. Unfortunately, David was starting to get a head cold—probably the same one some of our fellow hikers had on the Inca Trail. But we made it to our hostel, and booked a trip to a couple of the islands on Lake Titicaca for the next day through our hostel. We were also doing the calendar math in our heads, and starting to feel some stress about getting the timing right for a three or four day tour of Salar de Uyuni, while still getting to Buenos Aires in time for the flight we needed to catch.

It didn’t help that the wifi internet in our hostel refused to allow our laptop to connect, leaving us only with the small interface of David’s Android player to do any internet research. Nor did it help that the bathroom smelled pretty strongly of sewer gas, and had not been cleaned very well, if at all, and the carpet was grungy enough that Lana didn’t feel comfortable going barefoot (David never does, so he’s no gauge) in the room. Also, the paper-thin door opened onto a common room where other guests were talking and watching TV. And the single-pane windows faced a busy street full of cabs that were apparently propelled only by the sound waves from their horns. All of this culminated in a combination epiphany/melt-down for Lana, in which she realized that a $27 room was too cheap—or at the very least, this $27 room was too cheap. Using only the tiny Android player, she managed to find a good looking hotel nearby. It was around 9pm, but we headed back out to see if this hotel had any rooms available—we’d already packed our bags in the hopes that we’d find a place. The kind gentleman at the front desk said they only had one room left, and then he wrote the price down on a piece of paper—it would cost us $70. While $70 per room was a little more than we hoped to budget for this portion of our trip, it could have been a $700 room (ok, no, but $170). Unfortunately we’d left our passports back with our bags at the hostel, so we couldn’t effectively check in until we’d left the hostel. But Lana made it clear that we would be back. We hustled back to the hostel, grabbed our bags, and negotiated our exit. In truth, the proprietress was gracious enough and refused Lana’s offer to pay for the room for the night, but she also disagreed with her about the cleanliness of the bathroom. But we paid for our tour the next day and returned to our new hotel with our bags.

We don’t want to exaggerate, but it did feel like stepping into a different world. The bathroom sink had hot water--a first for us since leaving Quito. It was intensely clean, peaceful, and unscented. We slept like dead things. I don’t think the pictures can do justice to the difference, but here goes:

Despite the awkwardness of returning to a hostel where we refused to stay the previous night in order to depart for our tour, we did just that for our tour of Lake Titicaca. Our first stop was the floating islands of Uros, which are made of peat and layers reeds, about 4 feet deep. They are anchored in water that’s about 40 feet deep, and when larger boats pass, you can see and feel the ripples moving through the island surface. Several families live on each island, in a collection of reed huts. Fascinating, but also very, very tourist-oriented. There is a different collection of floating islands on the opposite side of the lake where the locals have no interest in tourism; more power to them!

Our second stop was the island Taquile, which was beautiful. It is a self-governed island that is largely self-sufficient. We enjoyed a brisk hike up to the main village, about 450 feet above the lake surface, where we had lunch, and then hiked down to a different bay, where our boat picked us up. We struck up conversation with a couple from Manchester, UK, who are also travelling for a year. She’s a teacher, and can actually arrange a leave of absence; he was in IT, and was just as burned out by 24/7 on-call as David was. We had an hour-long boat ride back, which was a good amount of time for a nap. We’ve gotten quite good at sleeping on boats; the rocking motion is quite lulling.

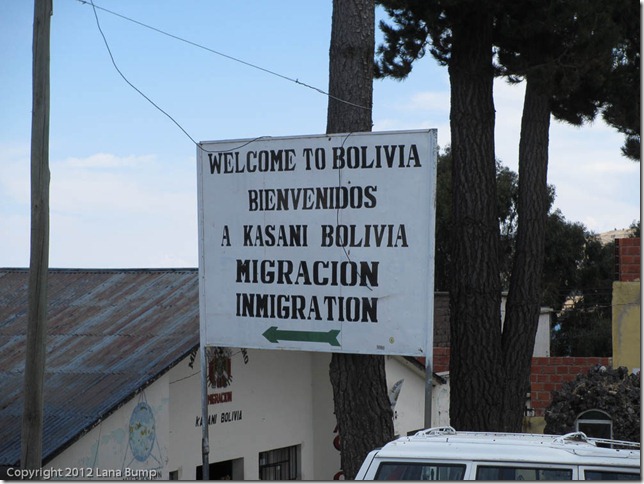

The next morning, we boarded a bus headed for La Paz, Bolivia, via Copacabana. We’d picked a tourist bus, specifically for the guidance they’d provide in navigating the border crossing. Like a few other countries, Bolivia has decided to charge United States citizens a ‘reciprocity fee’ similar to the amount that Bolivians need to pay in order to obtain a visa to travel in the US. They also require it in pristine US dollars—no rips or marks no matter how small—in exact change, which is a little tricky as the exact change requires both a $10 and $5 bill, which ATMs do not dispense. They sometimes require a yellow fever vaccination card, a visa picture, a photocopy of your passport, and an application form. Some of the former depend on the day and the person; only the cash is an absolute requirement. We had everything but the photocopy, which hadn’t been mentioned in any of our copious research on the subject, but the guide on the bus told us about it, and where we could obtain one on the Peru side of the border. In addition, we would also need a one Boliviano coin for an entrance tax on the bus—which we also hadn’t seen mentioned anywhere. Unlike the fairly swift, organized border crossings we’ve seen numerous times, this one felt like a scavenger hunt, with the clues being revealed at each subsequent stop. First we went to the Peruvian police station, and turned in our Peruvian immigration card. Then we left that building and walked to a different one, where we got our passports stamped for exit from Peru. Then we crossed the street to a money changer, where we tried to change US dollars to Bolivianos, but none of our spare bills were pristine enough (seriously, they have to be crisp, essentially uncirculated bills), but we were able to exchange our faded, wadded up, completely torn in half and taped with—I kid you not—packing tape, Peruvian bills for enough Bolivianos to pay our transit tax. This is also where we were able to purchase photocopies of our passports. Then, back across the street, up the hill, to cross the Bolivian border, and on our honor, went to the Bolivian immigration office. Our guide had told us there would be a long line, and to simply walk past it and say “I need a visa” which sounded sort of sketchy to us, but we went with it, and sure enough, the guard directed us to a completely different desk, with no line, where we nervously watched them examine every single US bill, feeling around the edges for minute rips. We also gave them visa photos, which we’d printed ourselves before leaving the US, and the visa application form, which we’d printed in Puno, and filled out already. And the photocopies. The cash was carefully placed in a till; everything else was tossed on a messy pile on the desk—they didn’t bother to attach the photos to the application forms. They glued a 5 year visa sticker in our passports, stamped them, and we were on our way, wiping sweat from our foreheads.

There was only one other American couple on our bus, who seemed to only have a nebulous understanding that they needed a visa. They’d read about the visa, but then read on the internet, or in a guidebook, that a visa wasn’t necessary. They only had $150 in cash of the necessary $270 that they would need. The guide on the bus suggested that they borrow it from us (hey thanks!) and then pay us back on the other side of the border. But we didn’t have enough (let alone pristine enough) extra cash to share. When they mentioned that, our bus guide paled a bit, and then switched to a plan B, which involved sprinting uphill a quarter of a mile with one of the pair to the only ATM near the border, and making multiple withdrawals to get the correct amount, then sprinting back to keep on schedule. They didn’t have visa photos or applications either; but the Bolivian immigration officer gave them applications to fill out, and there was no complaint about the lack of visa photos. There was never even a mention of yellow fever vaccination cards. It’s all about the cash.

After all the border excitement was over, we had a fairly short ride from the border to Copacabana, where those of us who were continuing on to La Paz had an hour layover before we changed busses. We found a café with wifi, shared a sandwich, and checked email to see if the hostel in La Paz had responded to Lana’s inquiry from yesterday. Nada, so she simply booked a different place that had an online presence. We’ve had zero response to email queries for accommodation or tours in South America; at this point, we’re done with even trying. If it can’t be booked directly online, or in person, it simply isn’t going to happen. After getting on a different bus after lunch we were on our way to La Paz again in a couple of hours. But just as we got settled down to dozing as the bus climbed through the curves from the lakeshore, we were interrupted by a ferry crossing. Still a little groggy from the post-lunch siesta, it was initially hard to follow the instructions, which required that we exit the bus, purchase our own ferry tickets (fortunately we still had sufficient Bolivianos from changing money at the border), and then watch the empty bus cross the Tiquina straight of lake Titicaca on a flat, tippy-looking barge. We hated to think about what kind of accident had forced this unusually (for the area) prudent precaution.

Lana had forgotten her camera on the bus, and was careful to be the first to board, which worked out well for us, as the young backpacker crowd took whatever seats they fancied, rather than the ones they’d paid for. Our bus ride to La Paz was another 5 hours. We were both exhausted, and David had lost his voice as part of the evolution of his head cold. Fortunately, the hostel we booked was a block and a half away from where the bus dropped us—thank goodness our first choice was slow to respond! It also has a pretty view.

Our first order of business was to buy the first of many, many Kleenex travel six-packs, as well as some orange juice and Sprite for David’s throat. Later, we walked to a surprisingly trendy portion of town, and had actual tea for the first time in South America. We don’t know what is contained in various ‘black’ tea bags we’ve tried, from Ecuador, Peru, and now Bolivia, but it produces something that is reminiscent of tea made by steeping a bad bag of tea for the fourth or fifth time. At Blueberries Café, it was actual loose leaf tea, and was wonderful. Unfortunately, Bolivia has zero restrictions on smoking in restaurants, and several of the tables were smoking, which was not a good combination for my sore throat and already dry eyes. We’ve seen essentially no smoking (except by tourists) in Ecuador and Peru, so it was really surprising to see it here. David’s fever was running around 101.5, so much of La Paz is a blur for him. We walked a lot, and it is a pretty town, though the streets are dangerous—not the people on them, but the streets themselves. Deep holes in the sidewalk are common, as are shards of wood or metal, and the occasional electrical line, at head height for a non-native. Also goods and food take up a large portion of the sidewalk, forcing pedestrians to weave on and off the busy streets. We saw raw trout being filleted on the sidewalk, as well as several milk crates packed with raw, plucked chickens, sitting in the sun on a hot afternoon. We mostly ate vegetarian here.

At this point, David was little better than a zombie, following Lana and trying not to do himself an injury while navigating the sidewalks. For this reason, and for others, we spent a good deal of the three days we were in La Paz hanging out in our hotel. David slept for a lot of it, and Lana watched movies and looked out the window and watched the excitement of the busy streets below. Everything you could possibly want to buy was for sale on the street in front of our hotel. Need to replace some underwear you lost when you had laundry done in Aguas Calientes? There it is on the street. Need to replace the pen you lost somewhere between Cusco and Puno? You can pick from three different vendors and 10 different kinds of pens. How about a remote control for your tv that you bought off the street that didn’t come with a remote? This lady just might have one that works. It isn’t just on the street, either. Apparently there are scads of knock off camping gear and equipment. While it may say North Face, and the store might have the logo up all over the place, it ain’t North Face at that price. We actually didn’t end up buying anything off the street, but it was interesting to watch.

There is also a witches market in La Paz, where you can apparently buy a spell or have your fortune told, or purchase a llama fetus to bury under your new house. It’s all there, and for a bargain to boot. (David just asked where the pictures of the witches market were. Lana explained that was not juju she wanted to mess with by taking pictures without permission.)

Lana checked with a couple of travel agencies for a tour of Salar de Uyuni, but discovered that the Bolivian 10-year census was going to occur on the following Wednesday, directly in the middle of our window for a tour, and it involved the entire country being on lockdown. No transportation of any type operating, no tours; essentially, everyone is supposed to remain at home for the day, and tourists apparently are required to stay indoors as well. We debated between giving up and booking a flight to Argentina, or pushing on to Uyuni, and attempting to book a one or two day tour from a local operator. Eventually we decided to push on, since we knew we’d regret it if we gave up. We didn’t realize that we’d also regret not giving up (there’s that foreshadowing again). We booked an overnight bus to Uyuni, which left around 9:30 at night. We just had to hope that we could book a tour from Uyuni, and that we had made the right decision to come to Bolivia after all.

Stay tuned for Bolivia, Part 2…coming soon.

No comments:

Post a Comment